Journey Through Albania, 1939 (1)

Journey Through Albania, 1939

Since its inception, the blog “Albanian Chronicles” has been passionately committed to a true mission: exploring the depths of libraries, bookstores, and the vast digital world in search of anything that could tell the story of Albania, its history, and its culture. This dedication has led us to share numerous articles from prestigious magazines across different eras, providing a broad and detailed perspective on how Albania has been perceived and portrayed over time. Today, we are excited to share with you a rare document: an article from the renowned magazine “Tempo,” dated December 21, 1939, offering a snapshot of Albanian life during that period.

Due to the length of the article, we will be publishing it in parts so that you can fully appreciate and absorb every detail.

Enjoy your reading and travel back in time through the pages of history!

On August 19, His Excellency Foreign Minister Count Ciano, accompanied by His Excellency Benini, Undersecretary for Albanian Affairs, inaugurated the public works that marked the beginning of the new Albania. In Tirana, Durrës, and Vlorë, crowds of Albanians from all walks of life demonstrated their loyalty to the representative of the Fascist Empire. Days of enthusiasm swept across Albania from end to end: after ten centuries of struggle, a secure future was in sight.

Journey Through Albania[1]

Part One

Photo-text by our correspondent Lamberti Sorrentino

Tirana, December.

To secure a seat on the Rome-Tirana flight, one must book four or five days in advance. At the airport, there are fourteen of us, but only twelve seats are available.

“This happens every morning,” a representative from Ala Littoria tells me. “Every morning, there are two or three hopefuls waiting — people who have reservations for the following days but still show up here, hoping that someone will miss the flight or arrive late, freeing up a seat.”

There’s a general, dressed casually in a uniform with a stiff white collar. He bears four rows of chevrons and a war tattoo, his chest barely large enough for all his medals. We share a knowing smile; he doesn’t act superior — just a general of our times, a man among men. Thirty years ago, a Brigade Commander would have been regarded with distant admiration, like a rare collectible.

Two young Roman men, looking like they’ve had little sleep, are discussing how pleased they are with the new ordinance reopening dance halls. “At least we managed to squeeze in a dance before heading back to Albania,” they say. They’re engineers at the Kupirola chromium mine. I’ll meet them again later on, covered in fresh mud, shoveling dirt in the early morning light. Most of the Italian engineers here are from Piedmont, and I couldn’t help but think, influenced by the imperialistic literature of democracies, that they should have been British, Belgian, French, or Dutch. But no, we have our own too.

And many: "There are about fifty of us in Albania," shout the two young men into my ear. Meanwhile, the mechanics have started the engines. In front of me, a beautiful mature Albanian woman takes her seat, dressed like the ladies who frequent grand international hotels. She is accompanied by two young women, one brunette and one blonde: one calls her aunt, the other calls her mother. Perhaps she can't hear because she has stuffed cotton in her ears and gazes into the distance. The engineers had danced with them the night before; they are all in high spirits. I believe these three Albanian women had come to Italy to take part in the festivities — at least, that’s what I gathered from their conversations, spoken in fairly clear Italian. When their Italian fails them, they rely on French, which the engineers translate for them, kindly and persuasively. The girls find a way to reveal that their Italian is suited almost exclusively for discussing the two crowns — Italian and Albanian — now united. Before saying goodbye in fluent French, it's clear that these three well-educated Albanian women, part of the Westernized world of diplomats and foreign legation staff, fit right into this world. As with everyone else, it's obvious that they are returning to Tirana, socially rejuvenated by their stay in Rome, now even more prestigious.

At the last moment, a captain from the Guardia di Finanza arrives: he greets the general, shakes hands with the ladies, and speaks to them in Albanian. He sits beside me. He wears just one ribbon, the knight's cross. Is it possible that within the Imperial Armed Forces there exists an officer who hasn’t fought even a single war, not one? I strike up a conversation, and he tells me in affectionate Italian that he was an officer in King Zog’s royal guard. Now he’s part of the Albanian army, merged with the Italian forces.

The past is not forgotten: in the city of Krujë, Skanderbeg’s tower still stands as a reminder of the bloody battles fought by the Albanian people against the East, battles that spared Europe from harm.

“Did you command Italian guards and officers?” I ask him.

“Yes,” he replies.

“Everything going well?”

“All is well,” he nods, satisfied, almost puffed up with pride. I notice the stars on his uniform: yes, indeed, our silver five-pointed stars. This is the Empire, I think. Back in the time of Paullus and Pompey, Albanians — then called Illyrians and Epirotes — were integrated by Roman consuls. And back then, too, there were Illyrian and Epirote decurions and centurions who held command positions within the legions of the capital. In fact, there was even a Roman emperor born in Durrës: Anastasius I.

“And when were you made a knight?” I ask the Albanian captain. Smiling with satisfaction, he responds:

“Oh, before the union. I translated some of the Duce's speeches into the Albanian language.” I ask him if he’s Catholic or Orthodox.

“Muslim,” he says, and then adds quietly:

“The three women are also Muslim. The lady was born Turkish and married a former deputy from Elbasan in the Constantinople Parliament.”

I glance at the other four passengers whom I hadn’t noticed before; their collars are turned up, and they've stuffed their ears with cotton. If I could only talk to them, who knows how much I might learn about Albania before we arrive.

This funerary stele is part of the archaeological complex known as the Nike of Butrint, discovered in Butrint, in southern Albania, alongside other highly valuable artifacts from various excavations, largely due to the Italian archaeological mission led by the late Ugolini. These are testimonies of Roman colonization in Albania.

Near Petrela, a characteristic Muslim village 15 kilometers from Tirana, famous for the tomb of Scanderbeg's adversary, the renowned Balaban Pasha, stands a castle of Venetian origin. Among the castle ruins, on the edge of a ridge, lies this abandoned old cannon, a reminder of ancient battles.

It is exactly nine o'clock when the plane lifts off the ground: it’s raining. As we ascend, the perimeter of Rome rounds out, the domes flatten; every element of the city loses its significance, except for the squares, which maintain their vastness. The rain pours heavily, and you can see the asphalt gleaming on the main roads. The gardens shrink into dark green patches. From above, nothing monumental or beautiful remains of Rome. Just a different perspective can change things, even those considered eternal. We enter the clouds, a dreary gray mass that separates itself from the sky, resembling worthless debris. The plane cuts through this muck; here comes a thick, gloomy bank of clouds—it feels as if we are drowning in it. A dirty, yellowish end-of-the-world light sticks to the windows. Half an hour of blind flight: melancholy. Then, more clouds, but now they are beneath us; we are in the clear sky. The sun streams through the windows, smiles return to faces. The Albanian captain opens a map: it’s the flight route from Rome to Tirana, with circles marking the two capitals, connected by a dotted line. The captain places his finger about a third of the way along the line, indicating where we are. He is well acquainted with this route. We are above Bari. Aviation is now for everyone, yet one cannot help but think that by train, from Rome to Bari, it takes eight hours. That's how long we took with the journalists following Count Ciano last August. That journey comes to mind. Three months ago, and it was a different world. There was no war then; in fact, back then, even those who believed war was inevitable didn't really believe it.

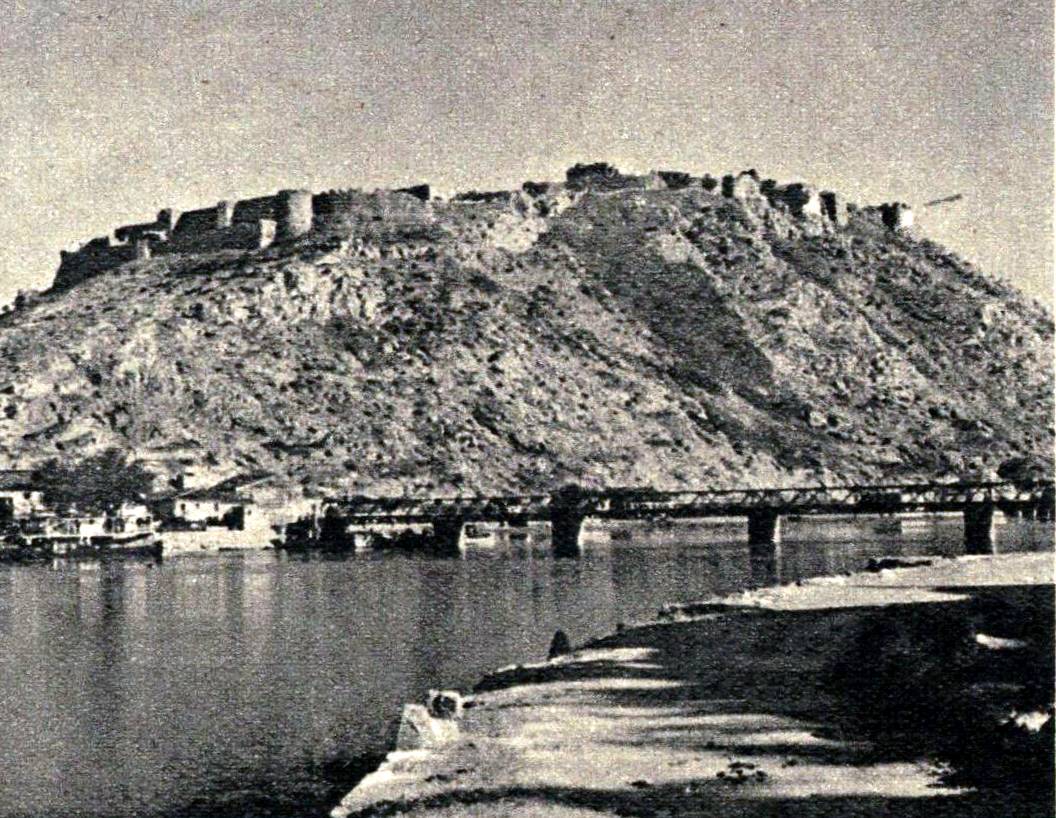

In Shkodra, the city in northern Albania, near the Yugoslav border, there are remnants of famous fortifications, with layers of overlapping civilizations: Byzantine, followed by Venetian. The fortifications of Rozafa Castle are well-preserved. It is remembered that in 1474, the Venetian commander Loredan repelled the assaults of a 30,000-strong Turkish army.

Across Albania, the signs of Venetian rule are still visible. The characteristic architecture of the maritime Republic can be recognized even among the renovations carried out in various periods and under various influences. Noteworthy are the bridges, boldly spanning the Albanian rivers from one side to the other; many of these bridges are still in excellent condition today.

A complete history of Italians in Albania has yet to be written; however, it is certain that today’s events will reconnect with historical milestones and propel this story into future prominence. Here is the first automobile to appear in Albania in 1913: it carried a group of Italian pioneers who intended to establish brick factories in Durrës.

Fascism has been present in Albania, not only as a doctrine and moral force but also as an organization, since the early years. Here is an interesting document: the foundation of the fascist group in Durrës, which took place at the Italian consulate in 1927. At that time, fascists abroad came to Albania; today, Albanian and Italian fascists are united.

They were splendid days. Joy and exuberance spread throughout Albania, from one end to the other, like the echo of ringing bells. Joy and confidence united the peaks of the Scutari mountains with the stagnant waters of Butrint: from north to south, never in Albanian history had there been such uniformity of approval. Albania, even before it was called by that name, was born as a bridge and lived as a pier, a landing place, a transit warehouse. The Romans, skilled road builders, upon reaching Brindisi via the Appian Way, did not concern themselves with the sea; they crossed it, and upon landing, right in front of Durrës, they placed a marker: on the west side, they engraved "Appia," and on the east, "Ignatia." The Ignatian Way reached Byzantium and is still a living road today, unlike the Appian Way, which has become a ruin.

We won't be writing the usual chapter of history here, but we will observe that the Albanians cannot be a people that can live and prosper independently. There are peoples who inhabit lands where passage is essential, main roads necessary for the expansion of greater nations, vital corridors indispensable for the spread of powerful civilizations. Thus, Albania, which served as a passageway for Serbs, Montenegrins, Bulgarians, Greeks, and Turks — even if this transit took centuries — now, for the Romans first and the Italians now, holds the value of an extension beyond the sea. This is why the Turks came to Albania fighting, stayed there fighting, and left fighting; the Italians arrived in peace, and they will never leave. The Balkan peoples, even when they settled there, remained partly outside of it, and throughout the country, they couldn't settle: they wanted to conquer, not assimilate. Romans and Venetians held this land as protectors, and their rivalry was just the basic formula of the old imperialist technique. How things have changed, we will soon see. The Albanians, with all these peoples and races, chasing each other and fighting on their soil, eventually stopped understanding them. Italy wanted them to be independent; their government, ignorant of such governance, was nothing but a mistake in every sense. And one fine day, Italian regiments crossed Albania from end to end. The weapons practically remained idle.

This is contemporary history, and everyone knows it: when those regiments entered the cities, they didn’t fire machine guns; they played fanfares; they didn’t lower flags; they honored the Albanian flags with military salutes, and beside them, as equals, they raised the Italian flag. Along with the bayonets, or rather, on the tips of the bayonets, they brought a new morality, one of better social justice. Nothing was damaged: houses, possessions, people, churches, mosques, traditions, customs, inhabitants remained intact. There were no taxes, requisitions, or arbitrariness: there was wealth because there was work; there was justice because there was strength. Alongside the Albanian eagle, a powerful and just imperial eagle was placed. Beneath its wing, life is good. Beyond its wing lies lead, as both friends and enemies know. For the first time in all of Albania, there is certainty about today and tomorrow. Long live. Cheers. Let us tell Count Ciano our satisfaction in knowing we are at peace. Songs, rallies, processions, dances, and torch-lit parades. A birth certificate, a sense of dawn, spreading and contagious.

We journalists looked beyond the flags and the numbers: we looked into people’s eyes, to know the truth. Ciano and his entourage formed a group of white uniforms, a sight to behold. Long live the Duce, long live Ciano, the eyes of the Albanians were soft with trust, the trust of the naïve, made of instinct, which does not err, but which must not be betrayed without risk. Eyes, in a way, filled with astonishment. Where three months earlier there had been nothing but swampy and melancholic emptiness, constructions were emerging. Only the Italians know how to create quickly, and well. What was happening, what was taking shape in those days seemed like a miracle. Albanians and Italians were amazed; the Foreign Minister was happy. Tirana, Durrës, Vlorë: two feverish days: visits, inaugurations, ribbon-cutting ceremonies on tricolored banners that opened roads, shovels of lime on many cornerstones: a new first day of creation. From Vlorë, we were about to depart by plane for Shkodër. This crown of Albania is not a prearranged act, a political fiction, but a human reality; and it was pleasing to feel the friendly reality of the places and the people.

We did not go to Shkodër. The Foreign Minister left for Rome on his own aircraft. We journalists returned by sea. In the evening, the commander confided to us that special orders had arrived. What orders? we asked. Even in 1915, it began with similar orders, we understood. We were perplexed. There is always a desire to identify the moment you are living as a historic moment. Yet, that was just another moment.

To be continued...

[1] Tempo – Roma 21 dicembre 1939

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

0 Comments