To entrepreneurs, freedom equals goods from Greece, where they swap livestock for electronics and appliances.

Turning from the busy highway onto a secluded country road, I followed the rusty signs, leaving a cloud of dust and the noisy world of Yugoslavia behind, heading into the austere land of Albania. With each mile the road grew bumpier and narrower, Centuries fell away.

I call it a road for convenience’ sake. I wondered if it had been deliberately kept in poor repair to discourage invasion, a problem for Albania since the dawn of time. A few sticks of dynamite would have been sufficient to set boulders tumbling down to seal off the border.

It was New Year’s Eve 1990. I approached Albania for the first time, with a mixture of uncertainty and trepidation. As a foreign correspondent, I had lived in several communist countries, and this one had the reputation of being the most repressive and paranoid of all.

A country slightly larger than Maryland, with a population of 3.4 million, Albania was just opening its borders to the outside world. Under Enver Hoxha, who ruled Albania like a feudal fiefdom from 1944 until his death in 1985, the country became a Stalinist time capsule, one of the world’s cruelest dictatorships, where wives of disgraced party members were ordered to divorce their husbands, where beards were banned, where all foreign credits and business were forbidden, where religion was outlawed, and where criticizing food shortages could land you and your relatives in prison. Even tourists were unwelcome. As Hoxha put it: “Why should we turn our country into an inn with doors flung open to pigs and sows?”

I drove as far as no-man’s-land, between Yugoslavia and the border station at Hani i Hotit, and halted the car. Somewhere here was the epicenter of my world. Behind me, in the Montenegrin mountains, was the boyhood home of my father; straight ahead and 20 miles south was the city of Shkodër, where my maternal grandparents once lived.

The air was damp, perfumed with the scent of Adriatic flowers. My serenity was broken by a group of bedraggled travelers from Yugoslavia. They were hauling bags and suitcases along a lifeless, single-track road toward rolls of barbed wire and grim-faced guards watching Albania’s border. I stared at the travelers for a long time.

If my widowed paternal grandmother had not moved to St. Louis with her sons and daughters, I could well have been among those people lugging their suitcases to the border. But would I still be me? Was I one of them? This was to become my recurring fancy on my journey into Albania, which I would visit six times in 1991, just as the country was making its painful transition from communism and Hoxha’s demented legacy.

The border guard rolled back an iron gate and smiled at me. He showed me where to park, then climbed the steps into the dingy customs station. I followed.

Another group of men and women was leaving the first of a trickle of legal visitors to Yugoslavia, where they saw relatives from whom they had been cut off for more than four decades.

Wordlessly, a 30-something border guard leafed through my passport, lingering over each stamp as if it contained a secret code. When he was done, he passed my documents to another man, and then he shocked me by addressing me in flawless English.

“Come, let me buy you a drink while you’re waiting for your passport.” He had taught himself English by listening to foreign language broadcasts on the radio, a crime punishable by prison under Hoxha.

The guard led me away, and we sipped sweet coffee and a sweet Albanian Riesling in another room. He insisted on paying, a native instinct for hospitality I was to encounter time and again. And he did not protest when I placed a carton of cigarettes on his desk. With in minutes of entering Albania, I discovered that even the most Orwellian of dictators had been unable to suppress human nature completely. There was hope here.

Wanting to be at the center of things, I sped along the road toward the capital, Tirana, regretting that I knew so little about my ancestors. I had never inquired why my mother’s parents moved to Austria-Hungary, but undoubtedly they left for the same reason thousands of Albanians emigrate today, to search for a better life.

Mother’s parents and four brothers had died by the time she was in her teens, and she never set foot in Albania. She had to submerge her identity after she married into a Serb family, and after the communists seized power, she had no further contact with Albania.

Even after Hoxha died and revolution swept communism from the rest of Eastern Europe in 1989, Albania remained a country apart, still stubbornly communist, a land that had wandered away from the known world and meant to stay that way. Hoxha’s heir, Ramiz Alia, upheld the draconian tradition.

Only in 1990 did revolutionary waves begin spilling over into the Land of the Eagle, as the Albanians call their country. In July a crowd of 5,700 stormed foreign missions in Tirana, demanding that the government allow them to emigrate. In December students took to the streets calling for reforms; riots broke out; and the economy unraveled. The first alternative party was formed, and some political prisoners were released. Alia’s government was forced to stage multiparty elections; in March 1991 a pluralistic parliament was elected.

The Hoxha nightmare was finally ending. But I soon discovered that it would take years, perhaps generations, for Albania to catch up with the modern world. Driving through the countryside for nearly an hour, I saw no other cars. Now and then a Chinese-made truck, sheep-faced and indestructible, appeared in a swirl of dust ahead. Cows, pigs, ducks, and chickens-moving along the road with complete impartiality-slowed me down. So did wheelbarrows and oxcarts, which shared the road with peasants on foot and on donkey.

I saw three schoolchildren, no more than ten years old, standing by the road and stopped to pick them up. They wore a sort of school uniform, black dresses with red neckerchiefs. Unable to speak their language, I offered each of them a banana. They giggled nervously and declined to eat. I doubt if they had ever seen the fruit before. It was also my impression that they had never been inside a passenger car. They did not know how to sit, how to open the door. One of the girls just stared at me with her mouth open.

Shut away no longer, former political prisoners seek redress for their outcast families. Gjon Mark Ndou (above, in dark jacket) was jailed in a cramped cell for 25 years. For themselves and for the nation, says an Albanian intellectual, “they need to tell their stories.” In May government workers removed the remains of Enver Hoxha from his regal tomb (below) for reburial in a public cemetery.

As soon as I stopped the car and opened the door to let them out, they scampered down the mountainside as if they had just escaped from a spaceship.

The towns I passed through had a gaunt, untidy look; the shops were shabby and virtually empty. In one store all I found was two sacks of potatoes, four moldy cabbages, and a few cans of fish.

The experience underlined how much Hoxha’s socialist propaganda of progress was a piece of Balkan theater. Although the dictator had been dead for more than five years, his spirit lived on. In early 1991 Hoxha’s statue still dominated every city and town, his visage touched up to look handsome, wise, caring, and fatherly.

I entered Tirana just as the capital city was waking from its long sleep. Amid the faded grandeur of the main squares and streets, hopeful people talked of little else but politics.

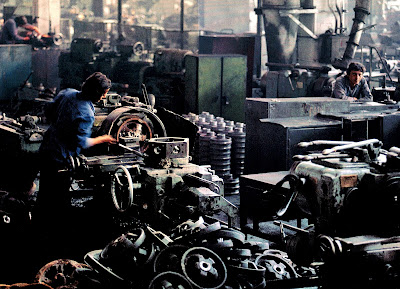

Tending Soviet- and Chinese-made machinery a generation old, a worker makes slow progress in a factory that converts scrap metal into tractor parts. The average weekly wage was only 250 leks-about five dollars-in early 1992, and unemployment approached 80 percent. Western economists say that undoing decades of Stalinist central planning will take another ten years. Even initiative has to be learned. Officials at the University of Tirana want to invite U. S. economists to help train faculty members. But, says a vice-rector, “We really have no idea how to begin to make contacts.”

A river of promenaders crests nightly in Tirana (above). With few telephones available, it’s the traditional way to catch up with friends. New to traffic, farmers in Shkodër (below) loaded down with cornstalk fodder can now freely market

Loggers, factory workers, students, and clerks stood in the middle of the street, chatting as if to make up for all the lost time.

Hundreds of them flocked daily to the offices of the new Democratic Party. This frigid perch-the villa that the communist government had given the new party had no heat was filled with earnest discussion about free speech, a foreign concept among people who for decades could not trust neighbors or friends with their inner thoughts. Workers came in to ask for help in organizing strikes, an alien notion in Hoxha’s Albania.

I was shivering in the office one day when a young activist named Arsem Kaustic walked in, clutched my arm, and would not let it go as he rattled on, with great indignation, about the communist thugs who were still at work in the countryside. They had tried to thwart his efforts to organize the Democratic Party in the small town of Laç. They had threatened to kill any reformers who ran for office. They knew no decency.

An old woman with faded blue eyes came in to tell me how Hoxha had enforced atheism. “He took my husband away more than 30 years ago because he was reading the Bible. My husband died in prison,” she said, sobbing. “Most of the priests were killed, or they died in prison. We kept our faith locked in our hearts-you didn’t dare discuss it with anybody.”

She left. A group of men burst in and an emaciated figure in a brown cloth cap began shouting. He announced his name, Gjelosh Gega, and his status: “I’m a political prisoner! I have been released! I wanted to come and thank the Democratic Party!”

He smiled a smile of pure joy, revealing a solitary tooth. The others had been rammed out by a border guard, Gega told me, when he and a companion had tried to escape Albania six years before. Gega, then 20, had been sentenced to 18 years. He was lucky. The guards shot his companion dead.

This new generation, I learned, wanted to erase everything linked to Hoxha. “Just look at our neighbors. They have all done better,” said Azem Hajdari, a stocky philosophy student from Tropoje who would later become a member of parliament. Within weeks of our meeting, Hajdari led students to topple Hoxha’s statue in Tirana’s central square, not far from a grotesque modern museum stuffed with the trivia of the dictator’s life.

“I want to turn that Hoxha museum into a giant disco,” Gramoz Pashko, an economics professor and co-founder of the Democratic Party, confided.

Once Albanians felt free to speak, the transformation from communism moved swiftly. By February 1991 strikes were breaking out, and protesters at the University of Tirana were showered with confetti made from the writings of Enver Hoxha, whose words had once been treated with biblical reverence.

“Enver,” the crowd shouted, “you are a thief! Where is our money?”

There is a small-town quality to Albanian life, so word quickly spread that my mother’s family had come from here. People came up to me, asking that I recite phrases and nursery rhymes from my childhood. Whenever I did, the response was the same-roars of laughter followed by an avalanche of words I could not understand. It was sufficient to guarantee acceptance, giving instant entry into a society that had spent decades perfecting its mistrust. They would smile at me as if to say, yes, he is foreign, but he is one of us. One of us. He has lived outside the prison, and maybe now we will too.

“Tell me honestly,” said one man in his early 30s. “What does the outside world think of us? Are we really so backward? Are things really so terrible here? Compared with outside? Please tell me honestly.” He huddled down against the cold in his black, worn coat, waiting for the answer.

It was hard to tell him that, yes, his country was very backward and very poor.

“And can we become a part of Europe; is the difference so great?” This question was from a woman. Sure, I told her, with time. I judged her to be about 40, but I could not be certain; her pretty face was marked with deep worry lines. They looked permanent.

My newfound friends included Bushy the waiter, always in a bow tie and always ready with a joke. (“I was named for President Bush,” he said.) There was the telephone operator Raymonda, elegantly dressed because her husband, Sophocles, sometimes drove his truck up to Yugoslavia and came back with many valuable goods. And vivacious Flutra, planning a fall wedding. (“You and your wife are invited,” she told me.)

These new friends helped me understand Albania. Bashkim, a Democratic Party activist, invited me to the first coal-miners strike, at the Valias mine outside Tirana. When I arrived in my Mercedes-Benz, the miners turned, cheering and whistling. They pointed at the car and flashed the V for victory sign.

“What on earth did you tell them?” I asked Bashkim later.

“I told them I dream of a day when this courtyard is filled with cars like yours, all driven by miners!”

But other activists had a more realistic grasp of Albania’s fluttering economy. “God save us from having power,” said my friend Gramoz Pashko, who could see that Albania had stopped working for the moment, poised between socialism and a market economy. “It will not be easy to change a system that was completely collectivized,” he told me.

Not a single private café or shop brightened the grim Tirana streets as the winter of 1991 slipped toward spring. Indeed, peeking in the doors and windows of the capital’s work- shops, I often saw women hunched over their labor like figures out of Dickens, working sewing machines in the dark, pedaling furiously to keep the needles going.

In the follow-up to Albania’s first multi-party elections, the country entered a new stage without properly marking the end of the old one. Key opposition figures, such as Sali Berisha and Gramoz Pashko, had themselves been members of the Communist Party just a few months earlier.

And even though the communists won 65 percent of the votes cast in the spring of 1991, the election foreshadowed the demise of communism in Albania. The opposition swept virtually every town and city. Only in the countryside did the communists win. Ramiz Alia was still president, but he seemed to know that he was a transitory figure who could do little more than provide a sense of stability, spanning the regimes of the past and the future.

For most of her life, my mother was uncomfortable about Albania’s reputation as a weird and ghastly police state, and she seldom mentioned the place. But when she reached her 70s, a change occurred. Then she began to talk about her yearning to visit Shkodër, the city of her parents. In her imagination Shkodër became more attractive and exotic than any other place she had visited-the Great Wall of China, the Vatican, the Grand Canyon. Shkoder was in a category of its own, to be spoken of with a great deal of pride, a special flourish. She never made the trip.

By the time I arrived there, in early April, the city was a mess. Protesters jammed the streets, arguing that communists had won elections in the countryside, where two-thirds of the people live, through intimidation.

“We are short of everything from bandages to heart valves,” says a doctor in a Tirana emergency room, who treats a head injury as best he can. Scarce medicines come largely from European and U. S. donations. Feeding time seems sweet in the maternity ward, yet mortality rates remain high because of scarce equipment and inadequate nutrition for pregnant women. Each year desperate parents are forced to seek treatment for 70,000 malnourished children.

A bonanza for eager young hands, an abandoned car is stripped clean. These youngsters are the first in two generations to grow up with the trappings of Western pop culture. For them, T-shirts sent by émigré relatives are the rage. Meanwhile, their toys are where they find them-even an empty box (below).

Police opened fire, killing four young Democratic Party activists and injuring dozens of others. The crowd went wild and burned down the Communist Party headquarters. Black smoke coiled from the building as I drove into town, passing an armored vehicle, overturned and gutted.

I liked Shkoder’s defiant spirit, perhaps a remnant of the pride that made this city the capital of ancient Illyria, whose last king, Gentius, was defeated and taken prisoner by the Romans in 168 B.C. The city’s history is the torturous history of Albania. After Rome, Byzantium held sway here, followed by waves of conquest by Goths, Serbs, Bulgarians, Normans, Venetians, Ottoman Turks, Italians, and Germans.

One legacy of Ottoman rule is that Albania is Europe’s only predominantly Muslim country. In 1967, when Hoxha declared Albania an atheist state, roughly 70 percent of the population was Muslim, 20 percent Albanian Orthodox, and 10 percent Roman Catholic. Hoxha’s fierce attempts to eradicate all religions served to reinforce the religious tolerance that has existed for centuries.

I found the people of Shkodër to be hospitable and friendly. I struck up a conversation with Marash and Domenika Selmani and asked about my Grandfather Gjurchu.

“Never heard that name,” said Marash, giving the same disheartening answer I had encountered all around town.

“Well, how about Kosmaçi?” I asked, trying the name of Mother’s aunt.

“Of course!” Marash answered with a smile. “The teacher Pjerin Kosmaçi in our school. We’ll take you to him.” Following an alley, we came to a tiny row house on Skanderbeg Street. I saw nothing familiar in the face of Pjerin Kosmaçi, the teacher who lived there with his wife, their infant son, and Pjerin’s mother.

Our host was wary. Coffee was brought out, platitudes spoken, and gradually a thawing and a disappointment.

“I’m really not your cousin,” Pjerin said finally. “I think your cousin may be Jack Kosmaçi, who lives

near Durrës.” Could I have Jack’s telephone number?

The word “telephone” produced an outburst of convulsive laughter. My host, his 71-year-old mother, and my friends Marash and Domenika responded like actors in a television sitcom scene, repeating the word and laughing and rolling their eyes. The phone-of which there were only 6,000 in the entire country-was the symbol of highest privilege. None of those here. But Pjerin offset my disappointment by scrawling Jack Kosmaçi’s address on a piece of paper and handing it to me.

I would get there as soon as possible, but first I was eager to meet Pjerin’s neighbor and cousin, a Roman Catholic priest named Simon Jubani.

He was 65 and very frail from the 26 years he had spent in one of Albania’s harshest jails. But Father Jubani was still capable of the fierceness that made him a national hero. Not long after his release in 1990, he confronted the government’s ban on religion by leading dozens of townspeople to the local church. Guarded by young Shkodër men with knives, Father Jubani stood in the weeds among longneglected tombstones and began to intone Shkodër’s first public Mass in more than two decades. By the time he finished, thousands of people, Muslims as well as Catholics, had packed the cemetery and spilled into the streets. The authorities backed down, and Father Jubani’s church reopened.

He invited me into his office, where a framed photograph of his meeting with Pope John Paul II attested to his new status after the years of neglect. Father Jubani knew the future would be very trying.

“It is difficult to pass from a tribal state to a democracy,” he told me. The transition would take time, but Albanians had already demonstrated their resilience. He reminded me that even Hoxha could not destroy religion any more than he had destroyed one of the strongest attributes of Albanian culture-besa, or the promised word.

“When Enver Hoxha came to power, besa was besa,” Father Jubani recalled. “But Hoxha tried to replace it with corruption, lies, and ignorance.”

Ah, besa. I recalled an old saying: “The Albanian will sooner kill his son than break his vow.” As a child I had heard the phrase spoken with a solemnity beyond all others, and I had been taught to honor my word, no matter what. It is still burned in my brain and lives in my soul. Until World War II, Albania had been an essentially tribal, feudal society, glued together by the traditions of family and loyalty - and always besa.

In old Albania besa was not merely a moral code, which, in other societies, forms the foun- dation of virtue and ethics. Besa was a law that served for centuries as a regulator of daily life. It governed business transacted by individuals, by villages and clans, or even by districts. To break one’s besa was not only the greatest disgrace but also subject to the most severe punishment-execution by one’s peers.

An Albanian friend of mine named Chim Beqari, who helped me drive through the mountains and acted as interpreter, would often point out the ruins of homes of those who broke their besa, where foundation stones were scattered as required by the unwritten law. Albanians no longer punish one another that way, but it gradually dawned on me that many people were still reluctant to promise me anything, no matter how small, such as fixing a light in my hotel room, perhaps for fear of making a vow that could not be honored.

Driving from the rugged mountains toward the Adriatic coast, Chim and I finally came into Shijak, the village where I hoped to find Jack Kosmaçi. He might be my only living link to Albania.

Carrying a bottle of French brandy and a box of good tea I had bought as gifts in a hardcurrency shop in Tirana, I crossed the village square to begin inquiries. One of the men there knew the family. “Ah, Kosmaçi the brick- layer,” said the man, helpfully pointing across the square to his building.

I stumbled up the concrete stairs, each step a different height, and found Jack Kosmaçi’s place. I studied him carefully for signs of the familiar. Had I seen those eyebrows, that slashing nose, in my family? He had a certain dignity, like the figures in old photographs on the walls of his apartment.

Lexamined a family portrait with 15 people. At the center was a military officer with a braid and decorations standing by an old man wearing baggy Turkish-style pantaloons and a vest with a big gold chain; two well-groomed young men stood by him in dinner jackets. The women were dressed in what must have been the latest Paris fashions.

While Chim explained my presence, Jack’s eyes drifted from the interpreter to me, back again, then fixed on me. We knew. He nodded and smiled and shook hands again, this time harder. We rapidly established relationships. Jack’s paternal grandmother was a Gjurchu, sister of my maternal grandfather. Jack was my cousin.

We talked all morning. Jack’s tale gave a wholly new dimension to the horrors of Hoxha’s era. I had driven past one of Albania’s notorious prisons, a place called Burrel, but now it became a real place, as did another named Spaç. Members of our family had served time in both.

Jack recalled the day they took his father, Anton Kosmaçi. It was 1944, and the world was still at war, but the Germans had abandoned Albania. Tirana, where the Kosmaçis were living, was already in the hands of Enver Hoxha and the communists. Jack was 15.

The soldiers knocked on the door and asked for Anton. He embraced Jack’s mother. He embraced Jack. There was no time for tears.

“Poor Mama,” Jack recalled. “She knew. She asked me to follow Father, but to keep my distance.” The walk to police headquarters took 15 minutes, no more, and every detail remains sharp in Jack’s memory: The sound of the men’s footsteps crunching on gravel, his father walking tall in a black overcoat with a thin fur collar, the boulevard lined with leafless old oaks and willows, the Lunës flowing cold through town, his father turning to wave before he disappeared into the walled compound.

Work or strike? Bulletins in the window of a Tirana office marked the birth of democracy, as general strikes in the spring of 1991 closed factories and mines. With all the equipment break- downs and strikes, lamented then President Alia, "Nobody works any more."

Anton was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment as an “enemy of the people,” ten years for each month he had served as minister of justice in one of the successive governments during the Italian occupation. Broken by the years in prison, he was released in March 1964 under a general amnesty. All the neighbors knew him as an enemy of the people, and they treated him like a leper. He died just a few months later.

“How is it possible your mother doesn’t know a thing about it? Didn’t anyone ever tell her?” Jack asked me. He poured another tumbler of raki liquor for each of us and scrutinized me, as if my knowledge of his father’s suffering might have eased the pain of all the lost years. What could I say to this sweet man with white hair? I never knew of his existence until that chance inquiry in Shkodër.

He understood. He gave me a smile and continued. “It wasn’t enough that Hoxha put my father in prison. The family had to be hounded into shame.” Jack’s mother was sent to a labor camp in Tepelenë, his grandmother to a prison hospital outside Tirana. Jack’s education stopped. The regime made him a bricklayer. The family’s final exile was to the village of Shijak, where I found them.

Jack’s two boys-Alexander and Blendialso suffered as the grandchildren of an enemy of the people. They were denied school beyond the eighth grade. Both became mechanics.

“I grieved, but that was how it had to be,” Jack said. “We were all living in a big prison.” He paused for a minute or so.

Kavaja Street, 5 a.m. Dafina Prifti is first in line at the milk-distribution store in her Tirana neighborhood. The supply varies. Sometimes milk is rationed, and other times there is none. Sometimes there is only powdered milk (if it hasn’t been stolen from foreign-aid shipments). The line may form as early as midnight for the sunrise opening. Last summer, when co-op farmers were granted a small stake of land, many took to working only for themselves. Co-op yields dried up, and so did food on city shelves, spawning rationing and sporadic food riots.

I saw a crack in his control as he struggled to continue. “Jackie, Jackie,” said his wife, Anna, who had been sitting quietly. When he resumed, his voice changed timbre, the anger swelling.

On June 1, 1990, Albania’s Children’s Day, Alexander’s two girls, age eight and nine, were to take part in a play for parents. Jack recalled: “They rehearsed diligently.

The day before the show, a member of the Shijak party committee came to school and told the director that Alexander’s girls had to be removed from the play.”

Enemies of the people. Jack paused for a long time. “To punish five generations! Five generations! What was the crime deserving of such punishment? There was not one specific charge leveled against my father, not one!

“I have to tell you the real tragedy,” he said, now almost in a whisper, as if he were letting me in on the very secret of life. “On the day my grandchildren were punished, my two boys vowed they would flee this land. Escape at any cost. How long are we to suffer? Even my grandchildren are not to be absolved?”

Both Alexander, 35, and Blendi, 21, made good their vows. They fled Albania in March 1991. “I’m not worried about Blendi,” Jack told me. “He’s young. He’s in Italy. Albania has good relations with Italy. We can talk on the phone at my post office.

“But Alexander…” He sighed deeply. “I worry about him every day. He has a wife and two children still here. He is in a Yugoslav jail where they keep refugees. He wants to go to America or Canada or Australia. But nobody accepts Albanians these days.”

I presented my gifts of brandy and tea to Jack and Anna and promised that I would try to help Alexander. My besa. Their eyes watered, and I realized that I had just given them the one thing they had secretly hoped for. I threw an arm around Jack as we strode out

into the bright daylight, like two cousins, followed by Anna, by Alexander’s wife, Rita, and her daughters. “Promise me you’ll return,” Jack said. I promised.

Throughout rural albania, I found people resigned to their lot in life, but from time to time they took small pleasures unknown under Hoxha. “We are trying to enjoy ourselves and not think about tomorrow,” said Namzo Guzin, a young farmer I met in the village of Borçë near the Adriatic Sea. Some of Namzo’s friends were getting married, and the whole community had turned out for an evening of fun.

“Tonight, we hope,” said Namzo, 35. “This is the first wedding I’ve attended. And this is the first glass I’ve raised to toast someone other than Enver and the party.” Namzo and his sister joined the others who were furiously performing the Napoleoni, a wedding dance named for the gold coins that guests used to throw to young couples in the precommunist era. No gold was to be seen here.

The toastmaster proposed yet another drink, which resulted in a genuine uproar. “It was a toast for our people abroad,” Namzo explained to me. “Almost everybody here has someone in Italy. The bridegroom’s brother fled in March, my sister’s husband in April.”

Living in Albania will be increasingly difficult. As the last months of 1991 set in, people were desperate. Hoxha’s legacy was broken, but so was discipline. Nobody was working. Indeed I met several mechanics from the former Enver Hoxha Textile Plant in Tirana who had not gone to work since March. Yet they still received 80 percent of their pay. The same arrangement applied to employees of the country’s sole glass factory, which had stopped production in 1990 because it could no longer get raw materials. One thing led to another. With a shortage of windowpanes to keep out the cold, schools, factories, and offices had been forced to shut down. And for the offices and schools still open, there was often no heat, as coal production ran short.

Food riots erupted in several communities. In Fushë-Arrëz, a timber town in the mountains, hungry protesters marched on the local food depot after rumors of an impending bread shortage. Twenty police were no match for a crowd of 2,000, which set the building on fire. More than 30 people died in the confrontation.

Albanian friends agreed that the food crisis was worse since the communists lost power. “Before, food distribution was kept going through fear,” explained one man who had been a senior government official. Now, people in the countryside were hoarding food, which meant that city dwellers in Tirana had to line up in the middle of the night for scarce supplies of milk the next morning.

“Even when you line up this early, you are not guaranteed of getting any milk,” an old woman told me. She needed it for her grandchildren.

The corn harvest will help see a farm family in the North Albanian Alps through the winter; their life is a backbreaking regimen shared by two-thirds of the population. Tradition dictates that bride Flutura Kadria, in a mountain village near Kukës, look distraught at leaving her family. Anything less would be an insult as they prepare to give her away in marriage.

Much of the countryside has been denuded for fuel, but in Fier some trees have escaped the woodcutter’s ax, and now and then a man can still bring home a fat goose from the market. Such simple pleasures are all that most Albanians can yet hope for.

Travelers were advised to take food with them on trips around the country. A Greek diplomat driving from Athens to Tirana was stopped, robbed of everything, and allowed to proceed with only his shirt and undershorts.

These traumas merely intensified the political struggle in Tirana. Albania entered 1992 spinning out of control. The Democratic opposition forces demanded new elections in the spring and won 62 percent of the vote, giving them control of the new 140-seat parliament.

Ramiz Alia, the last holdover of the communist regime, resigned in April. He was replaced by Sali Berisha, a founder of the Democratic Party and a charismatic leader.

Most albanians know what they want a civilized society, a market economy, parliamentary rule, and respect for human rights.

The country is entering a painful transition that could last for several years. The challenges are clear Albania has to overcome a defeatist psychology ingrained by years of repression, to pry loose the grip of the established bureaucracy in the countryside, to persuade young people (60 percent of the population is under the age of 25) to stay, to maintain religious tolerance, and above all to resuscitate a moribund economy.

There are a few signs of hope. Foreign investors are beginning to visit, seeing possibilities in Albania’s scenic beaches, snowcloaked mountains, and deposits of oil, chromium, and copper.

There are plans to develop the beautiful beaches along the Ionian Sea. But the coastal roads are scarce and in dreadful repair. Hoxha did not want this part of Albania populated, lest people would take it into their heads to swim to Corfu, visible in the distance. As I walked along one of the beaches, no other soul was in sight, but there were concrete bunkers and barbed-wire fences all around, Hoxha’s ubiquitous signature. It would take massive investment to bring tourism to life here, but it could be done.

Driving back toward the capital from the coastal town of Sarandë, I passed through a magnificent landscape dotted with olive trees and lemon groves. At Vuno, a tiny mountain village near the coast, I stopped to chat with a couple sitting on a terrace.

Could they visualize this place as a playground for rich tourists?

“Nothing is possible here,” the woman told me, laughing.

“But things are changing,” I said.

She laughed again and looked at me as if to say: “You do not understand.”

Her husband shot me an interrogatory look. “What has changed?” he asked. “Our two sons are in Italy. Let them look for their fortunes, and let them come back in joy. That’s our way.” They felt, in other words, that it was still impossible for Albanians to succeed in Albania. For them, good fortune was an import commodity, as it was for my cousin Jack Kosmaçi.

Driving back to my home in Belgrade, I recalled my promise to Jack. Alexander was still held in a Yugoslav jail, where he and other Albanian refugees waited for a review of their status by the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. When I phoned the U.S. Embassy, a consular official told me Alexander couldn’t get asylum in America. “Why don’t you try Australia? Or Canada?”

Canada agreed to take him, so I had the great pleasure of seeing Alexander released. I took him for a celebratory dinner.

Would he ever return to Albania?

“Never!” Alexander said. “I made a vow. The communists are still in power. Look at the leaders of the opposition-almost all of them former party members.”

That was true, I agreed. Everybody who wanted to succeed in Albania had belonged to the party, at least formally. But communism was dead now, the secret police gone. So was the old Albania. The new Albania could behad to be-different. The people would exorcise Hoxha’s ghost and begin something new, I insisted. Alexander quietly stood his ground. Let him go, I thought, he has suffered enough.

He’s off for a new life in Canada, where he will be joined by his wife and kids. When I told Cousin Jack about it, he seemed delighted by the good news but unsurprised.

Of course: I had given Jack my besa.

Lexo artikullin në shqip

National

Geographic, July 1992.

0 Comments