Albania today: two million souls ten thousand policemen (1965)

Albania today: two million souls ten thousand policemen[1]

Text and photos by Fernand Gigon

This is the first colour photo report made in Albania by the correspondent of a western newspaper. Having crossed the gates of the forbidden frontier, here is how today's Albanians live in the 'branch' of China that Mao opened on the shores of the Adriatic. The same myths and slogans of Chinese communism: heroic poverty, dedication to the state, fanatical nationalism.

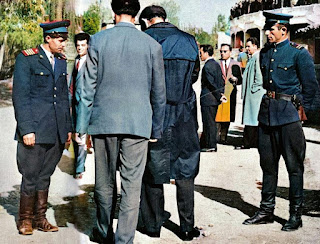

Two policemen check documents, just before a football match at the Tirana stadium.

Women are in the fields, men at arms, apricot trees in bloom and policemen everywhere. Sometimes the women leave the spade and take up the rifle, or vice versa. The only ones who leave nothing behind are the policemen in uniform, flat cap or goat's hair hat, or in plain clothes, i.e. in an Italian-made mackintosh. They hold 1.8 million inhabitants in such a tight fist, they guard it so closely, that no act of any citizen can escape them.

A group of Chinese technicians strolling through Tirana. The Chinese have taken the place of the Russians.

Among the many functions of policemen is to see to it that visiting foreigners do not stray from the group; there is that of sitting by their side in restaurants or in the stands of stadiums. The nightmare of these officers is that you manage to take a photograph of a scantily clad Albanian, against the backdrop, perhaps, of a new government building, or a factory under construction. The police, more than the political regime, keep Albania in a state of hibernation. It is incorruptible, and since murderers and robbers are quite rare in this country, it is mainly dedicated to political crimes. Punishments range from five years upwards, and are served in labour camps (surrounded by a curtain of silence and mystery) where brainwashing goes hand in hand with potato harvesting.

Portraits of today's 'labour heroes' on public display on a street in the capital.

Officially, there are ten thousand policemen on duty 'for the security of the state'. But then you have to take into account all those who come to put their hand in front of the Leica lens, all those who wander along the borders, between Thethi, Kukesi and Zergani, to arrest refugees seeking escape to Yugoslavia. This policing attitude, this age-old distrust, is the fruit not only of the dictatorial regime but also of the five centuries of Turkish oppression.

Prime minister Enver Hoxha 1965)

No other country in the world, except Tibet, is so hermetically closed, condemned by itself to such asphyxiation. A nation that is within reach, and yet the most impenetrable in Europe. There are only two western embassies in Tirana: Italy and France. Turkey, the RAU, Ghana, Cuba, Algeria only keep diplomatic delegations there. And behind them the countries of the East, all except the Soviet Union.

Albania is today a Chinese loudspeaker aimed at the West, spreading a strange ideology, a little bit inhuman and a little bit messianic, but certainly lagging far behind more modern Marxist thought. The 'hard' and 'pure' of Western communism listen to it as a holy gospel, so that this ideology ends up undermining the foundations of the communist bloc far more than all the united attacks of our democracies.

For about eighteen years, the Soviets, in order to have a foot in Albania, maintained an embassy of three thousand people, disproportionate subsidies to the government, a series of five-year plans, seven hundred scholarships per year to Albanian students, and fifteen submarines ambushed in the submarine caves of Sassano, a gun pointed at the American VI fleet in the Mediterranean, and especially at the ships cruising in the Adriatic.

The monument to Stalin in Scanderbeg Square (Albania's national hero) in Tirana. Here Stalin is still revered as he once was.

We do not know whether the Soviets, before leaving the country covered by an insulting campaign, had managed to win the gratitude of the Albanians. One fact is certain: that in the libraries, the only technical and scientific texts are printed in Russian, and that they must be referred to in order to operate the factories installed by the Russians almost everywhere. In schools, however, the teaching of Chinese is compulsory. The second foreign language is French. And in French, very correctly, the country's party secretary and dictator, Enver Hoxha, and with him the intellectuals, the men of his generation who learned French at the Korça high school or at the capital's Kyrenia school. After 1939, when the Italians arrived, the study of Descartes' language was replaced with the language of Dante.

A political propaganda board on the road from Durres to the capital. The word partisë recurs in all slogans. The initials PPSH are those of the unique 'Albanian Labour Party'.

A few years ago, I met in Beijing four Albanians commissioned by the Chinese government to collaborate on the design of the five-year plan to be launched in 1968. They spoke perfect French and often evoked the years of their youth at the high school in Korça or at the language faculty of the University of Tirana. Currently, Paris and Tirana are on good terms, and even exchange teachers for a few weeks, but the Albanian government is always on its guard, fearing that excessive liberalisation of cultural exchanges could adversely affect the rigid local Marxism.

The Albanians' political, and sentimental, creed is encapsulated in one phrase: 'He who is an enemy of Yugoslavia is our friend'. Hence, the cult that Tirana still vows to Stalinism. Hence, the loyalty to the myth of the red dictator. In Albanian cities, the statue of Stalin stands majestically in the main square. To see others today, one has to go to China, or to Georgia, the Marshal's homeland. In Tirana, his monument dominates Scanderbeg Square (national hero of Albanian independence against the Turks) and seems to defy every ideological storm. At the airport, Stalin towers over the bar and a series of commemorative photographs, with captions in Cyrillic characters.

Sunday in Tirana: football fans gather around the old mosque to buy tickets for the match.

Moreover, even the extraordinarily ugly government buildings, the council houses, the satellite towns surrounding the capital bear the imprint of Soviet architecture. The barracks style, sometimes with colonnades that support nothing, triumphs in the towns and villages. A bad taste, however, that has replaced in many suburbs the wall of rammed earth or kneaded clay and straw. Unfinished, however, is the colossal Soviet embassy, which the Albanians have not had time to admire. Yet, it cannot be said that the Russians did not leave traces of themselves through the countless expert consultants, engineers and technicians who came from the Urals or the Volga. They were the first to awaken this people from its long slumber, they instilled in it a way of life that can be found in the bureaucracy and the police. And now the Chinese are trying to change these habits, to communicate their own.

Another political manifesto extolling the union between workers and peasants. Nine out of ten Albanians live off agriculture.

Seen from behind, the Albanian officer resembles a Russian officer in every detail: the same severe uniform of dull green, the same visor cap with red green or blue ribbon, the same golden epaulettes, the boots that reach the calf. Moscow School instructors have long taught Albanian recruits the new art of war. But not of guerrilla warfare, too dangerous. To become a fantaccino, artilleryman or tank man, the young call-up takes two years. Three to become an aviator.

It happens, on the way down from Tirana towards the sea, to come across soldiers in training. They march in single file, by the side of the road, or drag a campaign cannon up steep paths. In these manoeuvres, which would seem ordinary, the partisan who sleeps in the bottom of every Albanian is awakened and turns him into one of the best soldiers in Europe. This was well known by the Italians, and later by the Germans, who suffered their deadly ambushes and sudden machine-gun attacks.

Boys in a suburb of Tirana. The city today has 140,000 inhabitants. The living standard of Albanians is considered the lowest among the countries of the European communist bloc.

Liberated by its partisans, Albania dedicated a cult to them that still endures. Literature, painting and sculpture celebrate their exploits. In the small museum in Durrës, for example, a third of the canvases on display recount the partisan epic. In the cemeteries, the graves of the fallen are decorated with stars that blush amidst the greenery of the parks. The word 'partisan' is found in the names of streets, cinemas, schools, collective farms and workers' clubs. 'Lavdi', meaning 'glory' is the key word of Albania. It is painted, drawn, sculpted, sung, written everywhere. It has the power to exert a kind of permanent mobilisation of the country. Here, it seems that the war has just ended. The former collaborators with yesterday's enemies, twenty years after peace, still have no right to vote, and the national anthem begins with the words: 'This red flag that united us in the struggle...'.

Fanaticism and patriotic passion often replace every other virtue of the Albanians. Here, every man who is young and robust-looking wears a uniform. But perhaps this is a false impression, because it should not take so many soldiers to form an army of just 25,000 men framed in three divisions, to drive 150 tanks and pilot a few dozen Soviet Migs. If the presence of the army is obvious to the foreigner, it is even more so to the Albanians, who see in it their main strength.

Young Tyroleans outside a cinema showing the Italian film 'Il ferroviere' by

Pietro Germi. Italy and France have the only two western embassies in Albania.

It is to the army that it would fall the task of opposing an invasion, should Yugoslavian annexation aims over Macedonia, or Greek annexation aims over Northern Epirus, become a reality. In fact, as soon as Hoxha senses that the country is slipping from his iron fist, all he has to do is conjure up the ghost of his neighbours to find unanimity around him. It is a form of nationalism that even explodes, with primitive violence, in international football matches. Hoxha uses it in the same way as missile parades, which for the first time this year appeared in a military parade in Tirana. They are Soviet-shaped missiles, but Chinese-made. The ramps are located in the mountains, a thousand metres above sea level, and are capable of launching a rocket with absolute precision over Ro- ma as over Sofia or Belgrade.

An anti-American poster about Vietnam.

The military is one of the aspects that best illustrate Moscow's decline in favour of Beijing, The Migs, for example, delivered by the Russians at the time, cannot fly for long without spare parts. The Chinese manufacture them, but in insufficient quantities. The motorised units, consisting of Siz or Skoda vehicles, have disappeared. And today the 175 kilometres of paved road are abandoned to civilians, donkeys and farmers' carts. As for the soldiers, forced to go on foot, they have returned to their true nature as mountain guerrillas, in perfect accordance with Mao-Tse-tung's theories and tactics.

At the time of the Sovietisation of Albania, the Russians kept three thousand people in Tirana. The Chinese, on the other hand, content themselves with two hundred specialists, who moreover have the power to make themselves invisible, and if they drive through the city centre they do so with the curtains down. Rather, China's presence is felt through other signs, in the slogans for example (placed on every tree or telegraph pole along the entrance road to Tirana) extolling Sino-Albanian friendship.

The ice cream cart.

Even the landscape has taken on a Chinese air. These bare fields, these terraced hills with stunted saplings planted at the summit, I remember seeing them in the Swechwan, or around Chuking, with programmatic writing drawn in the ground.

An aspect of traffic in the centre of Tirana, here regulated by two officers. The bicycle is still the most popular means of transport in a country where motorisation has only just begun. On New Albania Avenue, the main artery, a car passes every twenty minutes.

Here, too, one can read, on a hill of blossoming peach trees, the inscription 'Lavdi PPSH' meaning 'glory to the Albanian labour party'. The slogan stands out clearly against the sombre green of the trees, composed as it is of thousands of white stones or lime-painted bricks. An inscription that can be read from miles away.

Another writing ground are the boundary walls of factories, the facades of farms, the pavements and asphalt of roads. Wherever our eye rests, it is sure to encounter a written word: struggle, glory, committee, workers' party, heroic, partisan, and so on.

What is lacking in Albania, however, is the spoken word, direct communication, or rather the courage to communicate without awkwardness, without fear, Here is an example. On a road, towards evening, two workers are doing some running, they walk briskly. When I am level with them one of them asks without looking at me: "Do you speak German?" and then without waiting for an answer he adds in German: "Do you have something to sell?" Then, again without looking at me, he walks away with his companion at a brisk pace.

Contact with the foreigner, here immediately recognised, is avoided even by diplomats and high officials. If at a restaurant you happen to see the wife of an Albanian leader together with a foreigner, rest assured that it is an official invitation, by order of the Party, and not a private relationship, of personal sympathy. Albanians and foreigners are, even at home, divided by invisible curtains.

Durrës: a poster for the complete works of Mao Tse-tung published in cheap editions at the cost of a few lek (one lek is worth about 5 lire).

Enver Hoxha himself rarely appears in public. His position as First Party Secretary allows him to stay away from cocktails and embassy receptions. He lives a very modest life, as do his ministers, officials and generals, who have neither private cars nor service personnel. A marked austerity, or rather a collective poverty, accompanies these men in every action of their lives. The communist regime, after twenty years of exercise and dictatorship, has only achieved two things: first, to evolve the country from a state of misery to a state of poverty; second, to force the Albanians to work. It matters little if by dint of scapegoats and slogans, but the result is undeniable.

A bust of Stalin in the square main city of Durrës.

Now it is a matter of progressing to a level of decency, and to get there, the Chinese have devised a series of five-year plans that they take out of their wallets like so many miracle recipes. Beijing has offered Tirana a prefab factory, a cement factory, a textile factory, and a chemical fertiliser factory. But since they have no experience in this field, the Albanians have asked the Italian government for the necessary workers. Beijing will then pay the bill.

Regardless of whether new factories are built or not, Albania remains a poor nation, with nine out of ten inhabitants engaged in agriculture. The salary of a skilled worker is 6000 lek, that of a university professor 9000. A labourer or clerk with his 4000 lek per month can barely afford a pair of shoes. Rent and taxes are minimal, but food, if you go beyond the level of corn and cheese, weighs heavily on the family budget. For meat, there are queues at the shops, especially during the Easter holidays, when lamb and mutton are traditional dishes on the table.

The new Palace of Culture in Durrës, The building houses a theatre, a museum and a concert hall. Durres (42,000 inhabitants) has tobacco manufactures.

The Albanian woman queues to get a rare quality of fish, because her government sells it to Italy. In return, her husband has to queue for a stadium ticket, which the union provides at reduced prices. It is a scene that can be observed in the centre of Tirana, between the new Palace of Culture and the old mosque, where football 'scalpers' gather under the complacent eye of the guards. If you don't have a ticket, you will end up following the game in one of the 70,000 radio listening seats, scattered all over the country, or at the cinema, where Sofia Loren competes with the Chinese partisans of the 'Long March'. In the countryside, the Koran has given way to Marx, but the customs and habits of the fathers have remained unchanged, the women with their faces half-hidden by white headbands, ready to flee into the houses at the arrival of a foreigner, often barefoot.

Together with those in Beijing, Tirana's policemen hold the record for uselessness. On the New Albania avenue leading down from Stalin's statue to the University, the street is over twenty metres wide, but except for a few lorries and buses, only two or three cars pass through every hour. Yet the traffic warden waves his white stick and blows his whistle to get passers-by to cross.

This capital city devoted to compulsory cleanliness, devoid as it is of traffic, kept clean by a few elderly sweepers, seems asleep. It resembles a set of reinforced concrete, marble and right angles, from which the sudden explosion of a drama is expected. In fact, this small people of mountain dwellers, who elaborate a petty communist idealogy, devoid of demagogic fumes, feels today at the centre of the world, related to the six hundred million Chinese.

Indeed, in this respect, Tirana can be said to have faster reflexes than Beijing. Its analyses of world events precede those of the Chinese Communist Party, and the Zëri i Popullit often surpasses the Genmingibao. However, no doctrinal text or document for Party activists is published without the imprimatur of the Chinese.

In the Scanderbeg Square, a colossal building under construction proudly displays its marble colonnades and surreal steps. It is the Palace of Culture. In its shadow thrives the small trade of a few old women who have set up public weighbridges; mostly women go up there, anxious to check for the modest sum of one lek whether it is possible to get fat in a country so poor in food and delicacies.

New Albania, Tirana's main street, extends towards the University. The latter, visible on the horizon, is a legacy of the period of Italian rule, erected by decision of the government of the time.

In a series of display cabinets, passers-by can admire colour photographs of extraordinary technical quality, which no other westerner can see. These are images of China's first atomic bomb, born on 16 October 1964 in the Tsai-Dan desert, captured at all stages of production, from research to the explosion of the 'mushroom cloud'. Other photos show groups of Chinese students being charged by the police during a demonstration in Moscow; a clear sign that the photographer had already been warned by the provocateurs.

Like ancient Greece, modern Albania sells its olive oil to fight poverty and industrialise the country. On the hills of Dajti and Sauku surrounding Tirana, experts from Italy have planted three hundred thousand young olive trees. This oil is the currency of exchange with China, because Albania only has gold on the stars of the red flags. Apart from fruit, a little tobacco, a few minerals, its beaches, a beautiful landscape, Albania has nothing to offer the visitor.

On the other hand, it exports the bellicose ideology of the Chinese to Europe. And this is enough for Albania to be mentioned in the newspapers, and for a bit of its revolutionary doctrine, infiltrating millions of 'Khrushchevian' communists on both sides of the Adriatic, to succeed in sowing in some of them the seed of doubt, i.e., in Moscow's eyes, the most harmful disease of the spirit.

0 Comments