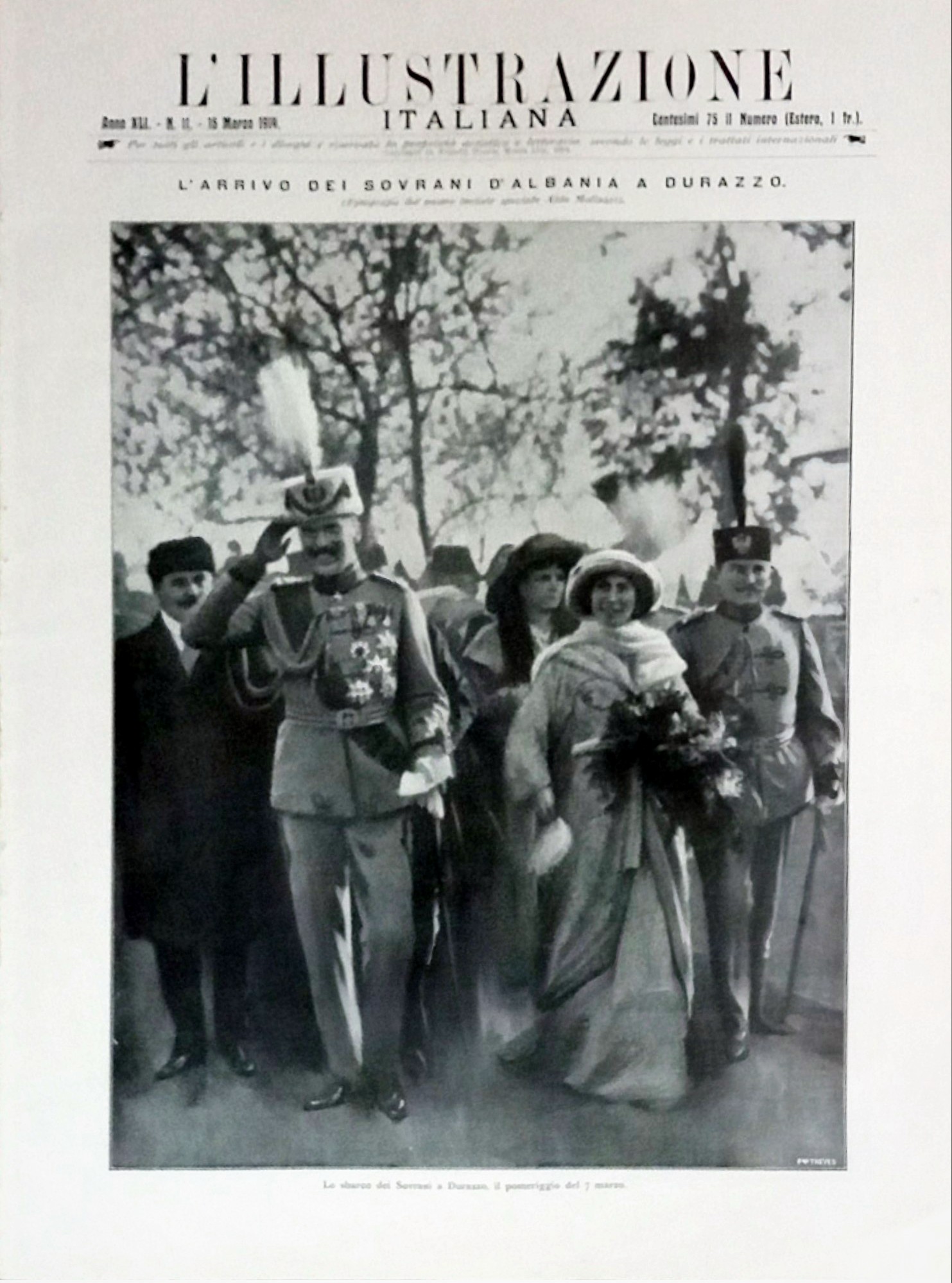

The New King of Albania on the Adriatic - 1914

A Historic Day

Giulio Caprin

Trieste, March 6, 1914

I had asked my dear colleague Simplicius, with whom I frequently collaborated, for a portrait—even an imaginary one—of the newly appointed ruler, Prince Wied, the Mbret of Albania. My colleague replied:

“An interesting subject, but difficult. At times, he seems distant in space and time: an anachronism mistakenly incarnated on the banks of the Rhine; even the most powerful camera cannot capture him accurately. Then, all of a sudden, we find him too close. And then my camera with a fantasy lens wouldn’t suffice: it would render him too ugly or at least ridiculous, which would be unfair. There is something in his situation that recalls the usual comic scenarios of the Balkan prince in operettas, but there’s also a certain romantic atmosphere of legendary royalty. Perhaps he dreamt of his unexpected crowned adventure with a pure heart—this man who has some shadow of pure Germanic fantasy in his blood: his aunt Carmen Silva calls him Lohengrin. And his destiny is serious, even if it was arranged by a not-too-serious will—the accord of the Great Powers. I dare not guess what truly lies within this new uniform: it could just be resigned automatism, but there could also be active faith. Thus, passion or at least illusion; yes, one or the other—two things that must be respected. If you really want to form a personal idea of Prince Wied, be content to look at him from the outside. Try to meet him at a good moment.”

The moment could not have been better. The moment when the new sovereign, by the will of the Powers and the grace of Essad Pasha, having completed his tour of visits to his many guardians and having heard the wise advice of his idealistic diplomats, finally appears in the figure of a Sovereign; he embarks for his kingdom, which he has never seen, but with the symbols of sovereignty recognized by those who gave it to him, he raises his flag above a ship which, although borrowed, is the ship of his destiny as a king. Now truly the Prussian captain, the German nobleman, begins to feel like an Albanian Mbret. They say Mbret is an Albanian abbreviation of Imperator—nothing less! It is the day that Wilhelm of Wied, even amid the confused and weary memories of many days of travel and banquets, will never forget. The preparatory duties end, and the expedition begins today in Trieste.

It could not have been anywhere else but Trieste. The Albanian adventure of the German prince, desired by Austria and Italy, accepted by Russia, tolerated by England and France, had to start here. Here is where the Western Latin world, the Northern Germanic world, and the Eastern world converge, in the Italian city of Austria. The Rhineland prince, who has lived thirty-eight years probably without ever considering that these great lines of history intersect over the Adriatic, might realize it today; and it would not be one worry less in the Balkan tomorrow under international surveillance. Certainly, here, facing the sea, he feels he is leaving not only the mainland but also the solid European civilization. But what exactly is this European political civilization in the name of which he must depart? In these days of travel, it has appeared to him too often in different uniforms and with different undertones. Let’s depart: Lohengrin is not afraid of the sea; the swan that will take him to ambiguous Albanian Elsa is a 1,300-ton swan that knows Eastern waters well: it is the yacht that previously served the Austrian ambassador in Constantinople, the Taurus. It awaits him, white, among a gray international fleet in front of the breakwater of Trieste.

Photo by Aldo Molinari: The Austrian yacht "Taurus" on which the Albanian Sovereigns traveled from Trieste to Durrës

In Trieste—what a coincidence—the Prince destined and the humble observer, who was curious to see him depart, arrived simultaneously. However, we arrived from opposite stations: the prince, who comes from the North, disembarks at the southern station; the Adriatic appeared to him suddenly at the exit of the Opicina tunnel from which the train plunges towards the city. Upon exiting that tunnel, the sight of this sea amazes and fills with anxiety everyone, even those who have seen it countless times. One feels precisely as though leaving one world and looking out on the threshold of another.

But perhaps the prince was distracted by counting how many cannon shots were meant for him—the first salute from the Santa Teresa battery. If not for the cannon booming, even the reporter arriving from the opposite station wouldn’t have noticed that Trieste was officially and internationally celebrating. This means that one can admire the black and yellow flags hoisted atop public offices—a rare joyful sight even in Austria, which commonly uses the white and red of peace for everyday purposes.

As for the people, in Trieste on a workday mid-morning, there are few who leave their jobs to witness an international and fateful embarkation. In the sirocco haze that casts a note of bleakness over its light stones, the city does not have an excessively festive appearance this morning. The celebration is almost entirely on the sea: flags atop the ships’ masts, colorful pennants on the rigging. Nothing more international in any port of the world than these flags fluttering like a multicolored laundry set out to dry; and in that confused fluttering of all colors, one cannot destroy the primary colors of the flags that declare the nationality of the ships. Is the Albanian flag among them?

Certainly: the double-headed eagle on a red field—and it is hoisted on the Taurus awaiting its guest. It doesn’t have to wait long: like a modest private traveler who, upon arriving at the port, goes to inspect a cabin booked by others, the Mbret must feel reassured, at least from this perspective. The Albanians who met him at the station had such a respectful air, like exquisitely civil people! Convincing others that it is a great thing to become Europeanized might not be impossible.

From my humble launch, I also allow myself the illusion of reviewing the squadron. The sea is full of buoys but very few policemen preventing us from getting closer… It is evident they are convinced that if necessary, the battleships can defend themselves. First, an Austrian dreadnought, the Tegetthoff, then the Zrinyi, then the Admiral Spaun—all Austrian. We are alongside the British Gloucester: on the deck are lined up bluejackets with straw hats—Mediterranean and spring attire—and the red tunics of the naval infantry. The Prince is visiting the British cruiser. There he is, descending from the command bridge. He is tall, yes, but not as tall as rumored ashore: it was said he was a man of two meters in height. It is not impossible, however, that his fine stature influenced the choice: it would fit that criterion of prestige that international great politics hold in high regard. What could a little man like Napoleon have done in Albania? And Wilhelm of Wied, I am assured, is also very strong: in his regiment, he could lift a colleague with one arm. Certainly, he will not bend under the weight of the responsibility entrusted to him, this sovereign.

Now, descending from the command bridge, he is forced to bend only due to his exaggeratedly tall stature, accentuated by the white plume that adorns his white headgear. The uniform in which he is dressed will undoubtedly make a great impression in Durrës. Here, one can admire only its political and symbolic complexity. The gray-blue fabric and the shape of the tunic undeniably bear a Prussian cut. But the arrangement of the black braids evokes to Albanians the idea of the embroidered cord braids on their jackets. In fairness between the religions that divide his subjects, the sovereign’s stripes were designed to avoid both the cross—be it Greek or Latin—and the crescent moon. As for the headgear, it is indisputably an Albanian white fez, somewhat embellished, let’s say; with that enviable charm that, if not Albanian, is certainly Balkan. Creating such a symbolic combination cannot have been easy.

Now the Mbret, so well dressed, with his lady who, at least she, can continue to dress like an elegant European lady, descends the gangway of the launch. He truly does not seem overly familiar with the sea: the unsteady gait of the man who undoubtedly prefers horses to waves gives it away.

Up close, he has a less Prussian expression than that generally portrayed in pictures. He looks around him a lot, smiles, and seems to seek out faces that smile at him. Perhaps he needs them. The princess, too, shows a kind of expansive embarrassment in her new royalty. Around their launch, now that they have descended from the Gloucester, and the gunner’s whistles propagate the order to prepare for salutes, there is no one. But the princess continues to wave right and left. She inspires a trusting sympathy: we respond with handkerchiefs and with a feeling less automatic than what is required by the duty of international courtesy. Those close to the princess today assure us she did not hide her anxious trepidation. Even the hearts of queens tremble. And before their visible trembling, one can no longer be a republican.

The prince spoke little but listened a lot. In all languages. The Mayor of Trieste spoke to him only in Italian, and the Mbret replied to continue because he understood. We hope that in Albania he will have ample opportunity to learn it even better.

From the Gloucester, he moved to the French Bruix. Another salute to the voices of lined-up sailors, more salutes, more gunpowder…

Our review is finished. In the international squadron here at anchor, neither Germany nor Italy is represented. This is one of those cases where the absentees are not wrong: absence here means more than presence. In Trieste—a city full of politics and international discourse, even when tangentially—it is much talked about Germany, which is not here yet is present. The Breslau—the German cruiser that for two years, who knows why, has always been a guest of the Adriatic—is in the San Marco shipyard; another German cruiser is in Pula. Everyone knows this. And everyone also knows that in this Albanian game of Italy and Austria, Germany is more involved than it appears. And Prince Wied, when he cannot precisely understand what so many well-meaning people unfamiliar to him want, will look to engage with the only ones he knows well: with Germany, the German prince.

Photo by Aldo Molinari: Essad Pasha with Colonel Philipp, the Dutch gendarmerie colonel, and the members of the Control Commission

As for Italy… a local humorous newspaper compares this international game to a game of briscola. The three players are an Austrian commander, a French one, and an English one. They would like to start the game here in port but notice that the fourth is missing. In fact, the “Quarto,” the Italian cruiser, which was under pressure last night in Venice at the Alberoni.

Trieste looks towards the open sea. The haze does not allow one to see far. Is the Quarto still at the Alberoni? No: it is much closer, between Piran and Koper, two or three miles offshore, just enough to not be easily seen today as the sea is misty. It would have been better if the Quarto had entered the port of Trieste. No, it’s better that it didn’t. Better for the police who must maintain order on land and sea. Many Triestines had arranged to rent a steamer to meet our ship, which cannot dock. These Triestines have such strange curiosities. The police, who had to give permission for the harmless little sea trip, have neither replied yes nor no: they will probably allow the trip to be made tomorrow morning when the Mbret, his escort, and perhaps the Quarto will be far away, maybe off Lissa.

But everyone agrees the Quarto should not come to Trieste, even Triestines who are too curious to see it, compare it, and say something to it. Since 1866, no Italian warship has come to Trieste. Austria will not have the right to complain: imagine that Trieste resembles Rome and that Italian battleships have the religious sensitivity that would prevent an Austrian Prince from officially coming to Rome. Even so, the alliance seems to prosper. The Zeit is wrong to grumble that the allied government is engaging in irredentism—excuse the forbidden word.

It is wise not to disturb obscenely the departure of this man who has no fear but has the right not to be excessively disturbed on this, his first day of Adriatic life. Is it possible that such complicated things must occur on such a small sea?

The Prince has no fear as he sails toward his uncertain destiny. He holds no prejudices. Before definitively embarking, he went to Miramar. Miramar, the castle of ghosts: the shadow of Maximilian still roams, who departed from here for death, and of Charlotte, who set sail for madness. Distant analogies come to consciousness on this historic day on this sea full of destinies. The Mbret returns smiling even from Miramar. Now he is wholly sovereign, boards his yacht, takes command, and orders the departure.

At five, in a modest light of the sun breaking slightly through the horizon’s clouds, the Austrian yacht and the two British and French escort cruisers set sail. Safe travels! Albania might be worth more than its reputation, and the ultimate result of so many discordant wills may not be a disaster for anyone. Safe travels.

Now the Quarto has come a little closer. From Koper, everyone watches it with a disappointed anticipation from which indomitable hopes are reborn. A very old man comments:

“It’s always like this: in ’48, in ’59, Italian ships were seen on the horizon; they crossed a little and then turned away.”

And another old man from Koper, a nobleman of ancient local nobility, has not made his walk in vain today. For years, he has gone to the pier to see if the Italian fleet might arrive. It never does. Today, the Quarto was in sight. It has disappeared. The old nobleman returns home in silence. More disappointed? Those who have made waiting the essence of their lives will wait longer. Long live the Mbret of Albania. To live on the Adriatic, one must never despair.

0 Comments